- Home

- Rita Gabis

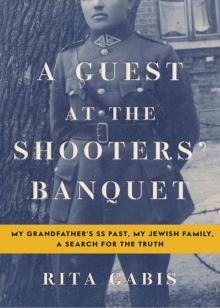

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet Read online

IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER

FOR ALL THE MIRELE REINS

We were riding through frozen fields in a wagon at dawn.

A red wing rose in the darkness …

O my love, where are they, where are they going

—CZESŁAW MIŁOSZ

* * *

Sventiány was remembered by the hussars only as the drunken camp …

Many complaints were made against the troops, who …

took also horses, carriages, and carpets.

—TOLSTOY

* * *

We were dreamers, now we have to be soldiers

—ABRAHAM (AVROM) SUTZKEVER

CONTENTS

* * *

A Note about the Text

Maps

PROLOGUE: Two Dreams

PART I

1 A Small Thing

2 Faye Dunaway as an Invaded Country

3 Word Gets Around

4 Bad Student

5 It’s Oprah’s Fault

6 Introductions

7 Fathers and Sons

8 An Education

9 Aunt Karina’s Pancakes

10 War

11 This Kind of World

12 A Good Get

13 Our Anne Frank

14 The Human Heart

15 Water

PART II

16 Yitzhak Arad

17 Animals

18 Mirele Rein/High Holidays

19 Chaya Palevsky née Porus

20 Messenger

21 Lili Holzman

22 Poligon

23 Day of Mourning and Hope

24 Artūras Karalis

PART III

25 Lost

26 Planners, Diggers, Guards, Shooters

27 Devil in a Glass Jar

28 The Translator

29 Railroad Town

30 Elena Stankevičienė née Gagis

31 Bucket

32 Devil’s Auction

33 Lucky Bird

PART IV

34 Bad Man/Good Man

35 Shooter

36 Inside/Outside

37 A Game of Life and Death

38 Mistakes

39 Anton Lavrinovich

40 Josef Beck

41 Illeana Irafeva

42 Work

43 Jump

PART V

44 January 2014

45 Šakotis

46 Gone

47 Given Back

48 Robin Fish

49 Witnesses for the Prosecution

50 The Company We Keep

51 Only God Knows

52 Memory

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

List of Illustrations

Notes

Bibliography and Archives Consulted

A NOTE ABOUT THE TEXT

* * *

AS I MENTION in the text, names of people and places in the borderland this book is concerned with vary widely in spelling and pronunciation. These variances depend to a large degree upon the source—Lithuanian, Polish, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and German primarily—in which the name appeared or in the particular usage of an interviewee. Although the standard for publication is to “silently correct” these discrepancies, the more interviews and research I did, the more valuable, even given the inherent confusion, the variances of place names and surnames became. They represent part of the rich essence of a multicultural borderland where people lived as neighbors yet had different names for their streets and their towns, for the food they ate, and different spellings for the names of their children. I have tried, as faithfully as possible, and I hope without too much trouble for the reader, to render place names and the names of individuals as they appeared in source material and as they were spoken to me. The complexity of rapidly shifting borders and the unique heritage of different population groups seemed best represented by these choices. Below is a truncated list of place names with their variations for three towns that appear frequently throughout the book. For further clarification, JewishGen.org is a wonderful resource.

Švenčionys (Lithuanian)

Sventzion/Sventsian (Yiddish)

Święciany (Polish)

Švenčionėliai (Lithuanian)

Nei-Sventsian (Yiddish)

Nowo-Święciany (Polish)

Vilnius (Lithuanian)

Vilne (Yiddish)

Wilno (Polish)

PROLOGUE

* * *

TWO DREAMS

DREAM ONE: I’M being hunted down. Whoever is after me and the reasons for their pursuit aren’t clear. I know they carry rifles. I know they have an instinct about small places; shelves with false backs that open into alcoves, shadows behind bulky furniture. They know where to look. They know how to listen for my frightened breathing. In the dream, my sense of the hunters is that they are methodical, zealous, unstoppable. They are after me; it’s a fact. Usually it’s night. I’m barefoot. Footsteps, heavy—slow at first and then louder, faster, clamor of voices, a sweep of light. I close my eyes, try to make myself invisible. My tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth, the spit sucked away by panic. The dream is one of the earliest I remember from childhood. I had it for years. Often, in those days, my hiding place in my dream was my own house, on Greenway Terrace in Kansas City: house of our cat Mitzi, house with the doorway from which my mother called me in at dusk in her broken English. What was Lithuania to me then? It was a rag wrapped around my mother’s tongue, the dark bread of the embarrassing sandwiches she gave my sister and me to take to school. The crust hard as the curb of a road, the meat inside an uneven slab. I wanted a white lunch. I wanted to sleep without dreaming.

Dream two: I’m a murderer. It’s not clear who my victim was. It’s also not clear that there is just one. I’ve buried whoever I’ve killed. I had help. There was planning involved in the placement of the graves. Often my dead are buried near a construction site, a place where concrete will be poured, where floors will be laid, where the dogs (Lassie and Rin Tin Tin, because again, this dream began in childhood) will sniff and paw at the ground, at the just-laid turf, at the stone steps and the hedge of fresh ground around the foundation. The dogs alert only to the ordinary; leaves, bits of gravel, the clanging of a copper gutter, the evidence of a recent rain. In the dream I’ve forgotten the reason for the killing. I just know that I’ve done it—and the knowledge folds over and over inside me like one of those combines in the fields outside the city, in Kansas where my mother’s brother and his wife had a farm, where my Lithuanian Catholic grandfather lived the last years of his life. The steel teeth rend me. Guilt, I’ll call it later, when I dream the dream in my twenties and wake trembling because this time the dogs and the detectives are pulling down wallboard, bringing the heavy machinery in to break into the truth, dislodge it.

“You’re very angry,” a therapist I was seeing at the time said. Her name was Eva Brown.

Eva Brown. Eva Braun. Hitler’s mistress is your shrink. Who said it? Maybe the lanky, drunk philosopher who bartended at the restaurant where I worked during college, maybe my Jewish father, who didn’t believe in therapists. Though he wouldn’t have used the word shrink. He would tell me the story again, of my paternal great-grandfather, Wolf Treegoob, an inventor and village elder who left Vyazovok in the Cherkasy Uezd (uezd means “county”) of the Kiev Gubernia for Kalnybolota in the late 1800s, at a time when Ukraine and Lithuania—and indeed, the whole of Eastern Europe—were teeth in the mouth of the Russian Empire.

Wolf Treegoob’s family name appears variously as Tregub, Trigub, or Tregubas, depending on where you look: a tax registry; a ship manifest; on JewishGen.org, the Vsia Rossiia business directory—a kind of yellow

pages that listed businesses throughout Russia, updated several times during its existence in the late 1800s and early 1900s; Yad Vashem’s Shoah Victims’ database; a three-by-five card typed out during his processing at Ellis Island—the last time he would use the name Trigub. When he moved to Philadelphia in 1908, the name would be forever Treegoob, a name I would one day touch on a plaque in a forest in Plugot, near the town of Kiryat Gat in Israel on a stunningly hot day, driven there in a car courtesy of the Jewish National Fund. The fund’s warm and informative representative Avinoam Binder arrived at my hotel in East Jerusalem and presented me with maps and a colorful version of The Book of Blessings for the Jewish holidays—a gift the serious young uniformed Ben Gurion Airport police in Tel Aviv would grill me about incessantly a week later (the luggage contents of noncitizens to and from Israel are routinely scrutinized).

“Anyone who had a problem would come to your great-grandfather for advice,” my father intoned. “That’s how it’s done. You don’t need someone to fix you. You don’t take your problems to strangers, especially someone named after Hitler’s girlfriend.” I seethed. I held up my love for Eva Brown like a flag. I buried the little seed of doubt my father had planted. Was she German? Was she corrupt, untrustworthy? She passed along no information about her personal life. I studied her dress; formal, stylish in a sedate way, nothing to call attention. Nice shoes. Skirts, pants sometimes but only with a jacket to match, or a sweater with pearls. I told her my dream of murder. I told her that every time I left the house, I panicked, fearing it would burn down behind me.

If my father were alive, I’d tell him what I learned about Eva Brown years after I stopped seeing her. She’s Jewish, like him. She’s a child survivor of the Holocaust. In her later life, transgenerational silence became a clinical and personal passion. I draft an e-mail to her that I’m too shy to send in which I tell her what I’ve discovered about my recurring dreams, with their ubiquitous motifs and durability. Whatever permutations of meaning they have in the immediate geography of my life, it turns out they are mirrors of what my grandparents on both sides of my family—Lithuanian and Jewish—actually lived. I, without knowing, dreamed parts of a truth about Lithuania. One part is this: my grandfather on my mother’s side was a murderer.

Or was he?

I

CHAPTER 1

* * *

A SMALL THING

WASHINGTON, D.C.

FEBRUARY 2014

On a freezing Wednesday morning I stood in front of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) division of Homeland Security, a few minutes early for my meeting with Michael MacQueen, a war crimes investigator. A storm was coming up the coast. My gloves hid in some crevasse of my bag. I clenched and opened my hands in the bitter air. The sky spread out in an even blue, and morning sun hit the glass doors in front of me. A hundred miles south, cars fishtailed on highways. Ice and snow crashed down branches and power lines. Here, just the barest scent of moisture in the harsh wind; the scent of rain, actually—unexpected in the deep heart of winter.

MacQueen was the first investigator sent by the Office of Special Investigations (OSI) at the Department of Justice to Eastern Europe in the 1990s. He was tasked with the painstaking work of sifting through archives for evidence against Nazi collaborators who had made false statements on their immigration and/or citizenship applications and were living quiet postwar lives in the United States. He went to Lithuania, where my Catholic maternal grandfather, grandmother, and their three children were born. He taught himself the language. He was, he would tell me, in the early days of his work there, always followed by two tails, one KGB, the other Saugumas, the Lithuanian security police.

Among the cases OSI made because of MacQueen’s tenacity and thoroughness, one involved a Vincas Valkavickus, who was deported back to Lithuania. There, during World War II, Valkavickus had been employed as a guard at a mass shooting of the Jewish population in the Švenčionys region, famous for lakes that make irregular circles on a satellite map, dark, as if they are solid matter interrupting the forests and meadows. In this same region my grandfather once lived and worked, before the war ended and he emigrated with a sister and my mother and her two siblings to the country where I was born. This country.

I pulled up the blue hood of my down jacket. The Holocaust Memorial Museum is six blocks from ICE. I’d been there many times, and was returning briefly after my meeting. Each time I traveled from New York to D.C., the contrast always struck me; D.C.’s buildings low squares, long rectangles of park, wide sidewalks soon, on this day, to be hidden by snow. I looked down Twelfth Street and gauged the quick, frigid walk to the museum; blocks of straight lines and hard turns. Still, I thought of a circle. I thought of my Lithuanian grandfather, all he might have hoped for as he wrote his name and the names of his children on the immigration form that sits on my desk. Did fear accompany his hopes? It was not an emotion I ever witnessed in him as a child, but then, I was a child.

MacQueen had explained in a quick phone call that when I got to ICE, I should go left to the Visitor’s Center. I pulled my hood back, ran a few fingers through my hair, and, forgetting his instructions, went in the front, through the wrong doors. I was quickly ushered out again to the glass door on the left. The friendly security officers scanned my bags and jacket, gave me a temporary pass, and offered me a seat.

A few days earlier I’d reread a write-up about MacQueen done under the auspices of his alma mater, the University of Michigan. A black-and-white photograph led the piece. A man, thin, hands clasped behind him, walked away from the camera on a gravel path lined with stones embedded with small plaques. A memorial.

The thin legs and straight narrow back of the man caught by the camera set up an expectation: here was the man I’d been exchanging e-mails with for months. Even more than our time together, it was this assumption that would seem, when I stood later in Union Station with frantic travelers trying to stay ahead of the weather, part of the circular and often errant nature of my own efforts the last handful of years. I’d expected the man in the photograph, but the man who opened the door from an interior hallway, shook my hand, and said “Labas”—Lithuanian for “Hello”—was someone else. MacQueen, but not the man in the photograph.

Expectations endure. During our conversation, MacQueen inexplicably remained both to me: the helpful, shrewd, wry man behind the cluttered desk and the unknown other. Several weeks later I contacted the photojournalist who had gotten credit for the image. She had no memory of ever taking the picture. Perhaps the editor of the piece got the credit wrong. A small thing. A lapse. A missing detail. Not really important, but it needled me.

Back in Union Station that late afternoon, I shifted my weight in the long, snaking line. All around me people unwound scarves, dismantled some of their armor against the cold; down and wool coats slung over shoulders, tucked under an arm. We juggled coffees, cell phones, bags, briefcases and, here and there, children. I thought of the wrong door I’d entered at ICE, of all the wrong doors I’d walked through over many months, only to backtrack, go a different way. I thought of how, very early on, trains, travelers, crowds of people ushered together, began to create a small panic inside me that has remained for every trip I take, every ticket punched, every stamp on my passport.

What I’d started with at the beginning was an incongruity—like the scent of rain in winter—in the history of my family as I knew it, in what was, when I began, the present moment, and what continues to be the storm of the past.

MY FATHER’S PARENTS came to the United States from Belarus and the Ukraine in the early 1900s. My mother and her family, Lithuanian Catholics, emigrated to the United States after World War II. The two sides of my family remained, through most of my life, separate—with the exception of a week or two during the summer when my mother’s relatives would come east to visit. Growing up, I thought this separateness was a simple issue of geography; my Jewish relatives lived on the East Coast, my mother’s Lithuanian family, after they

moved early on from New Jersey, were Midwesterners. I never imagined that their histories, their lives, intersected beyond a gathering for a birthday, a cookout on the beach.

In memory, my Lithuanian grandfather is tall and wide. He’s a wall. He’s a tree with low, spreading branches. Even though I knew him both as a child and a young adult, the images of him that dominate come from childhood. His hands, for instance, his right hand around my hand, the large fleshy enclosure, the calluses, the safety of it. I called him Senelis—Lithuanian for “Grandfather.” We’re walking somewhere—to the bakery maybe—in Jamesburg, New Jersey, where he ended up with his sister and my mother and her siblings after four years in a displaced persons camp in Germany at the end of World War II. It’s the early 1960s. I’m four or six or seven, on a street with only a few shops. It’s that lazy Sunday after-church time, in the spring. My coat is unbuttoned. Senelis doesn’t have a jacket on, just a plaid shirt, neatly tucked in. He’s freshly shaved. Maybe a white bit of shaving cream somewhere. The scent of it mixes with the smell of leaves and marshes. He shares a house—it’s more of a shack—outside town with his sister, my Krukchamama (“Godmother” in Lithuanian, which she was to my mother and became to the rest of us). It’s a wild place where rain pools and cattails grow. When the sun goes down, crickets call up from the crawl space under your feet in the little hallway between the kitchen and Krukchamama’s bedroom, with the crucifix above the bed and the lumpy mattress. Senelis’s neck, a little grizzled, is the only thing about him that looks old. He fishes and hunts. He doesn’t sit in a chair all day and read like my father. He’s a man who can move.

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet