- Home

- Rita Gabis

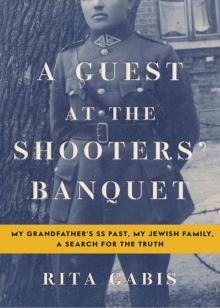

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet Page 3

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet Read online

Page 3

When I conjure up that young woman now, writing with intensity and suffering, perhaps in a room in Massachusetts on a side street three blocks north of Emily Dickinson’s house, or at an alcove desk in a suburb where I was once an improbable boarder, or in the sand on the beach at Martha’s Vineyard, jittery from the gallon of coffee I drank through my morning waitress shift in Edgartown, I seem astoundingly fortunate. I could write. I could rip pages up and start again. I had a room and a bed. I went to college. I worked and was paid. I lived in time with language. I was born.

I WAS RAISED in a secular household. We went to mass (without my father) on holidays with the Lithuanian Catholic side of my family and celebrated the Jewish holidays with my father’s side of the family. Yet when asked what I was, I always responded, “Jewish.” Technically I was not; my father had married a non-Jew. However, my Jewish grandmother, Rachel Treegoob Gabis, believed her will and wishes superseded rabbinical law and conveyed to me her notion of how I was to think of myself.

She made her pronouncement the summer I was twelve, on Martha’s Vineyard, where she lived the last half of her life and where, along with my parents, various aunts and uncles spent parts of each summer.

It was a hot day, and I was hanging out by the side of the local movie theater on the corner of Circuit Avenue in Oak Bluffs. A new poster was up advertising a movie I wanted to see. What was it? Jaws comes to mind, but probably it was another movie. The sun was bright with that salty white glare that only happens near the ocean. I was wearing a tiny gold-plated cross around my neck that I’d bought at the town drugstore because my summer girlfriends in Oak Bluffs (mainly Polish Catholic daughters of plumbers and rooming-house owners) all wore them. Absorbed in the movie poster, at first I didn’t see my grandmother drive up in her used gold Impala. Ignoring the traffic, she put her car in park, threw open her door, and made it to the curb where I stood before I could completely register the fact of her. She reached for me, tore the little necklace with the cross off my neck, and threw it on the sidewalk.

“I never want to see such a thing on your neck again,” she said.

I looked down at my ruined necklace, and then back up at her red face. She was always fiery, loving, dominating, but I’d never seen her so angry before.

“You’re Jewish,” she spat, then turned, jumped back into the Impala, and sped away.

IN THE CAFÉ with my mother, the ambient noise buzzed in my head. I felt hot, folded and unfolded my napkin as if it was one of the cards Senelis used to send me. He never learned to read English very well. “To My Dear Son-In-Law,” the front of a birthday card might say. Inside it, a worn-out five-dollar bill, his uncertain handwriting. “Anyting,” he’d said.

But he had said other things to me, too, when I was young. That I was not to be like my father, an admonition that caused me enormous distress until I could make out from my grandfather’s stumbling grammar that he wanted me to be a Catholic. I was eight or nine at the time. It was summer again. Oak Bluffs again. My grandfather had been drinking. We were alone on the scruffy side porch of my family’s rambling house built by a sea captain who designed the interior beams to be curved like those of a ship. Senelis’s eyes were round and glassy. I’d begun to recognize the appearance of that sheen as well as a haranguing repetitiousness that came over him and connect them to his beer breath or a half-empty bottle of too-sweet wine. His English always got worse when he was drunk. “No be like your fader,” Senelis said. Why? What was wrong with my father? “Jews no good,” he explained. I remember being both confused and relieved. It wasn’t my father completely, the whole man, who Senelis thought was bad, only one part of him. I had no idea why Senelis felt that way. I promised him I’d go to church, knowing that I wouldn’t. I knew also that I would never tell my father what Senelis said.

THE WAITER BROUGHT our check, and without me asking, or her telling me, I knew my mother had had enough of the past that day.

We walked out to Broadway. A man with a wide face on a bike with a food delivery, going against traffic, careened past. My mother chattered. We walked slowly past the gym, the fruit stand, a bus stop where eight or nine preschoolers stood, roped together by their cheery, watchful minders. The children gawked at the mannequins decked out in spandex in the gym windows—ready to run, leap. Question after question tumbled through me—all really the same question. Did Senelis hurt anybody?

THE NEXT MORNING my mother and I sat in my study in our pajamas. The one large window framed her in light. In her white nightgown, she stretched like a sleepy cat. We sipped our coffee. She tucked her knees underneath her on the old, elephantine sofa. I had a felt-tip pen and a piece of paper. I asked her to write down the name of the town where my grandfather had worked for the Germans. S-V-E-N-C-I-O-N-Y-S. She became again the language teacher she had once been, laughing a little at my difficulty pronouncing the name. She said it again for me, slowly, and then again. And then—stopped. Something was there:

She spoke dreamily. “I remember the grown-ups talking,”

Was Senelis there? No, he wasn’t.

“Something happened.” She reached for it, the past. “Germans had been attacked in a car, and there was a translator with them who wasn’t German. All the Germans were killed, but she lived. And I said to someone, maybe Kruckchamama and one of her friends, that was a good thing—she was alive! But they said no, better she had been killed given what would happen to her.”

My mother was quiet for a minute.

And what was that? I pressed.

“The Gestapo, torture … some horrible death.”

I waited a beat. “Who was she, the translator? Did you know her name?”

My mother just shook her head, as if shaking off the past, the emotional capital these moments of remembering cost her.

The translator. What happened? Was my grandfather there?

MY MOTHER RETURNED to Martha’s Vineyard, where she and my father had moved from the Midwest after retirement and before my father’s death from cancer. I missed my father terribly after she went. I wanted to talk to him about what my mother had said. I wanted to ask him what he thought of Senelis, if he knew anything about what Senelis did during the war. I wanted to tell him, belatedly, what Senelis had said to me on the side porch that summer.

Soon after my mother’s visit, on an Upper West Side morning, light refracting off every hard surface, I stood with our two dogs on 104th Street. They yanked on their leashes in the direction of a cabbie’s honking. A tall teenager (shouldn’t she have been in school?) in leggings and frizzy red hair passed, holding a bag from the McDonald’s on Broadway. The smell of salty grease made my mouth water. Half a block away, the corner market boasted white plastic buckets of flowers that looked like daisies dyed a garish blue, a fake purple. They probably were dyed. I thought about the amazing shimmer of a red maple I’d watched all fall in the park; the real and the not-real. I turned away— And there was my father walking up from Broadway toward me, a gray wool cap on his head. His stride was eager and determined. He’d never been a large man, but age made him more compact. The khaki pants. His air of distraction and curiosity, his sweetness. He got closer. Any second he’d look up. Oh, the happiness at seeing the missing one again! It surged up into my chest, my throat. Then my father turned a certain way, tilted his head to the sun—vanished into someone else, younger now, I could see, with a sharper chin, a different mouth. I stopped, let the man pass, vaguely embarrassed, vaguely demolished, but oddly joyful for the almost incarnation of physical shape, molecules, feet hitting the pavement, heart beating, lungs working. I see my father this way sometimes three times a week, sometimes once every few months. This would please him, I think, if he were living. “Really,” he would say, “really, you thought it was me!” This is a fact I’ve learned from his death, from the deaths of my grandparents, the deaths of friends—that the experience of their absence is something you end up wanting to talk about with those who are gone. And the questions—the particulars only they

can tell you, their secrets, a nuance of a story, shimmer like maple leaves with their palmate lobes, a fact of nature and time you’ll never touch, hold in your hands, crush.

IF MY FATHER were alive, I’d ask him about Senelis, ask him why, especially when my father got older and Judaism became central to him, he never spoke to any of his children about the way we were raised—with the trappings of two religions and the substance of neither.

If his mother, my grandmother Rachel, were alive, I’d ask her what being Jewish meant to her. If Babita were alive, I’d ask her what my mother was like as a child.

If Senelis were alive, I’d present him with my checklist:

Were you a member of the LAF—the Lithuanian Activist Front?

No answer.

Were you a member of a partisan unit in hiding during the Russian occupation of Lithuania?

Yes; check.

And when the Nazis violated the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and entered Lithuania in 1941, did you come out of hiding?

Yes; check.

Did you then become chief of police under the Gestapo in Švenčionys, Lithuania?

Yes; check.

He pushes his can of beer or glass of cherry wine to the edge of the waxy tablecloth. He whistles a little, as he did after scraping the scales off a fish he caught onto newspaper in the sun.

What did you do during that time? Who did you become?

He sighs. He rubs at a callus on the fat chuff of one of his hands, says my name, rolling the r, landing hard on the t, picks up the can of beer and in a glass meant for orange juice or whiskey shots, pours a little for me.

I E-MAIL THE Lithuanian Central State Archives in Vilnius, not sure what to ask for, not sure, at first, what I’m looking for. I ask for a copy of my grandfather’s internal passport during 1941, the document that’s supposed to show his comings and goings inside the country. I ask for the names of the Gulags where my grandmother served her time after she was arrested by the Soviet secret police or NKVD. I ask for any information relating to my grandfather’s activities as police chief in Švenčionys in 1941 and his brief arrest three years later. I ask for a specific file—a pay voucher for local police in the Vilnius district in 1941, submitted to the German command. I give the file number, the page numbers. Two weeks later I get an e-mail back. I’m asked to wire the equivalent of thirty-five dollars into a Lithuanian bank account. I’m told that after I do, there are three documents they’ll send me.

It’s the end of my teaching semester. True winter has set in. Snow stops the city. Juvenile red-tailed hawks in the park go hungry. Buses skid sideways on every icy avenue. Cars hibernate in hard-pack drifts. I get sick. Too sick to go to the bank and wire the money. I’m ill for weeks, feverish, my throat swollen. Every day I think about the wire transfer I need to send, the thirty-five dollars. I don’t send it. I don’t go out. The fever continues. Every day I think of the archivist in Lithuania with a stack of requests. If I ever get around to sending the money, she’ll have put my questions into the bottom of the stack. It makes me crazy. But I don’t go to the bank. Stupid woman, the archivist is probably thinking anyway. Her grandfather’s dead. Why put us to work for a date here, an accusation there? Doesn’t she love him? Doesn’t she have other things to do with her time?

For weeks the snow continues. For weeks I read and sleep sitting up because of the coughing. And the stack gets taller and the answers to my questions get farther away. Finally, six weeks after the archive’s request for money, I stop off at the bank after a trip to my doctor, who says, “Welcome to the age of the superbug.” She’s sick too, coughing in her little examining room, covering her mouth with her hands.

At the bank, the wire transfer takes all of ten minutes. That same day, I e-mail the archives again, inform them I’ve wired the money, give them the confirmation number. Weeks go by, I’m waiting. I want those documents. I hate those archivists in Lithuania. Hate the piles of requests with mine lost somewhere, shuffled into the did-not-follow-up stack or the took-too-long stack. I want my information, and I want it now. How American!

EVERYBODY HAS A secret. Everybody has a locked door, a dream with a message. In my family, I blurt the secrets. I jimmy the locks on the doors. All my life, I thought of myself this way. But somehow, during those homebound weeks, the weeks the money didn’t get wired, the follow-up e-mail didn’t get sent, I realized this was false. All my life I’ve said just enough to survive. I wrote just enough to step over the threshold of silence. Then I stopped.

I have no family members with whom I can talk about what went on in my life as a child, compare notes, affirm one another’s microversions of the past.

What redeems the brutality of the larger past, in the macro history that contains us all? Every day I ask myself that question. The only answer that ever comes is this: To make the past manifest.

WHILE I WAS sick and the snow fell and I shuffled around the apartment and our two dogs lavished their cold-nosed love upon me and my husband brought me soup and my stepdaughter told me to spit after I sneezed and the days went by and the weeks fled, it seemed more and more possible to stop asking questions about my grandfather. But when my fever spiked, the dead in my life pulled at me as if they were still here, as if Senelis still drove the horse and cart between two front lines, his children on a bed of straw behind the buckboard. He lived in me. He was a wheel that turned endlessly in my family’s path without any of us knowing, exhausting the road, running across the shadows of who we all were and who we would become.

I sent out another query to another archive in Lithuania and again, in a few weeks, got a reply:

“We … beg to inform you that in archival fund of department of Committee for State Security in Lithuanian SSR, in card index for operational registry files, there is a card which contains a record that Pranas Puronas had worked as a chief of Švenčionys police department during German occupation … If you wish to have us carry out a search for persons who testified on P. Puronas and for activities of Švenčionys police department as well as for related files … then we beg to inform you …”

“Yes, I wish you to search,” I wrote back right away.

CHAPTER 3

* * *

WORD GETS AROUND

“Everyone knew he was a Nazi,” Aunt Shirley said, when I phoned her about Senelis.

The list of living family members I am in touch with is small. Aunt Shirley, my father’s sister, is one of them.

“What do you mean by Nazi?” I asked, unhelpfully.

“Oh, you know, they all were, all the Lithuanians.”

Did she mean my mother too? Did she mean my Lithuanian grandmother?

“What did my dad say about it? What did Nana say?”

“We never talked about it. We just knew,” Shirley said.

“How did you know?”

“How do you think?” Her voice was louder by a few decibels. My obtuseness was starting to irritate her.

She lives thirty blocks or so away from me, also on the Upper West Side, in an apartment by Central Park that has grown cavernous since her third husband, the composer George Perle, died. Urbane, artistic, worldly—she used to frighten me a little when I was a child. I felt ignorant in her presence, Midwestern, simple. Her beauty has morphed into a diminutive elegance. She tends to laugh, a little caustically, at that which is dark. She gave a quick laugh now, a pause during which she considered how to tackle my ignorance.

“Everyone hated the Jews.” The decibels climbed again.

She sounded just like her mother—my grandmother Rachel—giving my father what-for about his right-wing politics, or imploring one of her errant grandchildren to take her advice. I suddenly felt like I was talking to Aunt Shirley and my grandmother at the same time: Nana, who could cut you off for twenty years if you betrayed her—not a phone call, a letter, a nod at a party—or claim you, as she claimed a number of troubled, broke, and talented artist friends of her daughter’s, lodge you permanently in her heart, as she did me.

Since my mother’s visit, I missed her as much as I did my father. Beyond the world of books and his political leanings, my father could be impossible to talk to. His mother was different. She was, like everyone, full of contradictions: unaware and intimate, coarse and gentle, self-possessed and haunted.

When I hung up with Aunt Shirley, I went to the rickety wooden cabinet in my study and opened a file of old letters. My grandmother had lovely penmanship before cataracts clouded the page of stationery before her. She pressed hard on the nib of the fountain pen she used, which left little blots of ink here and there, like space dust in the galaxy of her thoughts. Dearest, she began before she told me what I should or should not do—appreciate your father more, never forget how much your mother suffered, the family is your home. You belong here.

Grandmother Rachel, born in 1899. A century and change earlier, her birthplace would have been part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania instead of the ever-expanding Russian Empire.

She relentlessly stabbed at the eternal weeds in the sand and moss of her large yard in Chilmark on Martha’s Vineyard. When she reached her hundredth year and couldn’t stoop to the ground anymore, she dragged herself, seated with a collection of sharp instruments, from one defiled spot to the next. Before her lipstick kiss, she grabbed our cheeks hard enough to rearrange our faces. Pain and love were intermingled—her life, the lives of her children and grandchildren, depended on this knowledge. Otherwise, how could any of us prepare for whatever forces might be bearing down, preparing to extinguish us?

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet

A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet